No. He had me on his lap.

You were not raped; he raped you.

Memory moves as it can,

freedom is yours to place the verb.

and yes, the oppressor's language

sometimes sounds beautiful,

always dies hard.

Let us move on. — Margaret Randall

The journey that began on January 22nd, 2012 started as personal outcry. The diary I wrote on that day was an impulsive act of defiance against a culture of denial and ignorance about the reality of Child Sexual Abuse. It was also an act of public testimony to a private trauma. I never envisioned it would become anything more than that. Ultimately it did-not because of me, but because of the hundreds of people who responded and said “it happened to me too”. Or their mothers, their sisters, their brothers and their friends. The testimony of survivors, as well as those from the grave. Ghosts of the past emerged. Keep talking, they said. Don’t stop.

So over the past months, that's what I've been doing. Not just me, but several other people who have become involved. We have been working, day and night, on creating something from the ashes of tragedy-working on it long before we even knew what it would look like, continuing to work without the benefit of knowing what it will become-yet knowing somehow that it is absolutely necessary. That it is worth the sleepless nights, the triggers, the setbacks-it's necessary. It's not a choice-it's a calling. It's an obligation. You may have seen examples of some of the work we have been doing-In the diary Introducing TREE Climbers, I spoke about the journey we have taken so far, and what our vision was. I talked about my lost friend "Rosa", a girl who was abused in ways that defy the imagination, but still held her head high. Who still could smile and see the capacity for good, and wrote poems so beautiful that they made me cry even though she was considered illiterate and borderline mentally retarded.

I also said I was going to be rolling out a 5 part series on the history of child sexual abuse as a political issue. At the time, I had all but finished this series-and my plan was to put out one installment every few days. To build interest, momentum, and ultimately transform TREE Climbers into what we have envisioned- not just a support group, not simply a non-profit, but the beginning of a social movement to end the sexual abuse and exploitation of children.

But I only published Part 1-and then I stopped. And I haven't been able to bring myself to post the rest of it. People keep asking me why, so I'll do my best to explain.

I'm afraid. It's that simple, really. I've poured my heart and soul into this series for months. And more importantly, I'm not telling my own story here-I'm telling the story of others. People who have all been forgotten by history. And I'm afraid that I'm not going to do them justice. And more than anything I'm afraid that people won't care. Because I'm talking about events long past, involving something that you cannot even see.

And as history has shown us-being forced to see what has been kept hidden is often the only true catalyst for social change. For the civil rights movement, it was the murder of Emmitt Till. Emmitt Till was not the first boy to be given a death sentence for the crime of looking at a white woman. Nearly 3,500 African Americans were lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968. Many of these victims, like Emmitt Till, were children. When Emmitt Till was kidnapped, tortured, shot in the head at point blank range and then thrown into the Tallahatchie River with a cotton fan tied around his neck, he could have easily become another sad statistic. But his mother, Mamie Till Bradley, refused to let her son’s death go unnoticed. And more importantly, she refused to hide the truth about what was done to him. She held a public memorial service, and took the unprecedented step of showing his body in an open casket, in the same condition she found him. When asked why, her answer was simple: “I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby."

For the Vietnam Anti-War movement, it was the Mei Lei massacre. Hundreds of thousands of innocent Vietnam civilians, many of them children, had been slaughtered before the horrors of Mei Lei came to light. Returning veterans, in an act that was also unprecedented, joined the anti-war movement. They turned in the medals they were awareded for bravery and valor and gave public testimony of the atrocities of war, including their own war crimes. Despite the attempts of the Johnson and Nixon administrations to downplay the casualties and the human toll, with the advent of photojournalism the cruel and devastating reality of warfare was, for the first time in history, undeniable. And never was it more evident than when the photographs from Mei Lei were finally

published.

These are horrible images. Many decades later, they are still difficult to look at. But they served a purpose-they forced the public to confront atrocity, and the anger and outrage these images inspired became the catalyst for both the peace movement and the civil rights movement to reach their tipping point. By forcing the public to confront that which has been hidden, images serve as living testimonies for those who cannot speak for themselves. But what do you do when the atrocity is one that you cannot see? The sexual abuse of children is devastating and prevalent. But it is also very well hidden. The crime itself almost always takes place in isolation. There are often few, if any, physical signs of abuse. And unlike Emmitt Till, or the Mei Lei massacre, there are no images. The only photo documentation of child sexual abuse is child pornography, and to show it publicly would be a grotesque form of re-victimization. And even professionals who have to view child pornography as part of the investigative process often report being disturbed by seeing children giggling and smiling as they are being abused. Sexual offenders turn abuse into a game, and go to great lengths to get their victims to see it the same way. They point to the involuntary physical responses to stimulation as proof that their victims are enjoying the experience, and then use this as a way to keep them silent. This is especially effective with male victims, who are often afraid of being seen as gay. As Judith Herman writes in “Trauma & Recovery”:

“Participation in forbidden sexual activity […] confirms the abused child’s sense of badness. Any gratification that the child is able to glean from the exploitative situation becomes proof in her mind that she instigated and bears full responsibility for the abuse. If she ever experienced sexual pleasure, enjoyed the abuser’s special attention, bargained for favors, or used the sexual relationship to gain privileges, these sins are adduced as evidence of her innate wickedness. The child entrapped in this kind of horror develops the belief that she is somehow responsible for the crimes of her abusers. Simply by virtue of her existence on earth, she believes that she has driven the most powerful people in her world to do terrible things. Surely, then, her nature must be thoroughly evil. The language of the self becomes a language of abomination. Survivors routinely describe themselves as outside the com-pact of ordinary human relations, as supernatural creatures or nonhuman life forms. They think of themselves as witches, vampires, whores, dogs, rats, or snakes. Some use the imagery of excrement or filth to describe their inner sense of self. In the words of an incest survivor: “I am filled with black slime. If I open my mouth it will pour out. I think of myself as the sewer silt that a snake would breed upon” […}The profound sense of inner badness becomes the core around which the abused child’s identity is formed, and it persists into adult life"And this is the gravest injury that many abused children are left with. Physical wounds heal over time. That sense of “inner badness”, the feelings of being “contaminated” and “different” remain persistent and pernicious. Depression, feelings of worthlessness, self-injury, and despair can continue into adulthood. Ultimately, they can become lethal. Below the fold is my attempt to help you see those hidden injuries-and maybe help those of you who still don't get it to finally understand what we are fighting against.

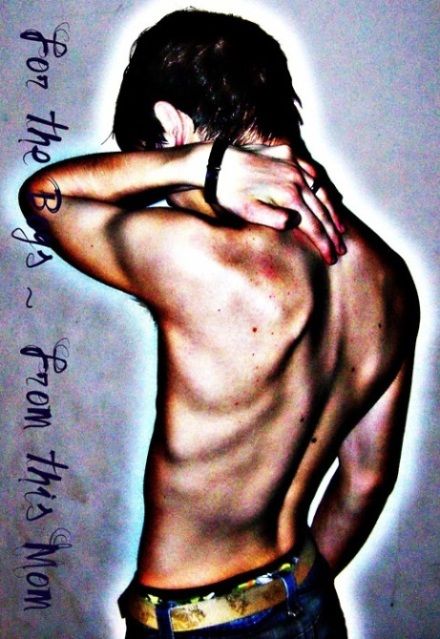

This is Vale:

This image is from the blog of my friend, For The Boys, From This Mom. Vale is 14 years old in this picture. He is anorexic. He is anorexic because he hates his body-because his body has been raped.

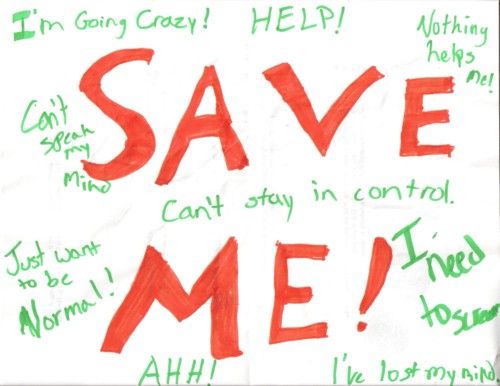

This is a picture that Vale's sister drew

In the words of her mom:

Do you have any idea how much I was leveled when I saw what she wrote? After sitting down with her and speaking with her, she expressed how she wished she could die. My 11 year old. Wants to die. Now I don’t think it’s a literal wish to kill herself, and she’s said that she doesn’t really want to hurt herself, but I think the expression of her heart is that she would rather die than continue the path that she is on. She is so continually afraid that Vale is going to die that she seems to be beside herself. She sits next to Vale during the school day, so when he wears a t shirt she sees his scarred arms, and that troubles her quite a bit. She has a very sensitive soul, so those scars are a constant reminder of the distress that Vale is in. Yes, of all my children, Dolorosa is the most dramatic. Yes, of all of them she would be the most sensitive, she can’t watch Monsters, Inc. because it’s too frightening for her. But still…to have such a heavy impact. Vale’s perp damaged that precious child so badly, but he’s damaged so many other people as well. It’s as if he shot Vale with scatter shot, and we are all collateral damage.These are the scars on my wrist from one of my 3 suicide attempts.

This is my face after my boyfriend grabbed me by my ponytail and repeatedly slammed my face into the wall of our apartment-breaking my nose, and chipping 2 of my teeth.

Neither of these injuries were directly caused by sexual abuse-but sexual abuse still caused both of them. Because it made me feel worthless-so worthless that I wanted to die. So worthless that I could love a man who would do that to me-I could ONLY love men who would do that to me. This is a Tree Climber and her sister

What you don’t see in that photograph is that those two little girls were forced to sexually abuse each other by their own grandfather. And they no longer speak. That little girl on the left is 43 years old now, slowly killing herself with alcohol.

What you don’t see in that photograph is that those two little girls were forced to sexually abuse each other by their own grandfather. And they no longer speak. That little girl on the left is 43 years old now, slowly killing herself with alcohol.This is all I have to show. At least for now. Sexual abuse only comes to the surface when those who have been victims of it speak out. And to speak out is an act of defiance-defiance, first and foremost against your abuser, who has often conditioned you into silence. Depending on the identity of your abuser, you are simultaneously committing an act of defiance against your own family and community. It is defiance against the human instinct to deny and repress human atrocities-something that operates on both an individual and societal level. It forces the bystander to become a witness- thrusting them into a conflict between victim and perpetrator where they are forced to choose a side. As Judith Herman wrote "It is very tempting to take the side of the perpetrator. All the perpetrator asks is that the bystander do nothing. He appeals to the universal desire to see, hear, and speak no evil. The victim, on the contrary, asks the bystander to share the burden of pain. The victim demands action, engagement, and remembering."

This is not just true of Child Sexual Abuse-it is true of every type of human atrocity. The need to deny, displace, sanitize and ultimately forget horrific events has been played out, again and again, throughout the course of human history. When the survivors voice is marginalized-when their status is already devalued (i.e. a woman, a child) it is easy to do so. Marginalized people can be discredited easily, and written off entirely.

Occasionally the voices of survivors become impossible to ignore though-and when that happens we may respond, but also rush to sanitize their experience and turn it into something more socially palpable that does not threaten the status quo. The atrocities of slavery were banished from our consciousness with the emancipation proclamation, and it’s empty promises of reparations. Native Americans were given their reservations. Returning war veterans get their GI bills, their parades and memorials. When these gestures fail to satisfy and that anger continues, the reaction is one of weariness and disgust-you got what you wanted, why are you still carrying on about? The anger of the survivor, their dissatisfaction becomes a testament to their own moral failings. It is assumed that they must simply enjoy being seen as victims.

And this is what I have to confront every time I write about it. Because I am not over it-I’m still angry. I can’t stop talking about it. And every time I do, I run that risk-I can hear the unspoken reactions in my head. Oh here she goes again, talking about this. She must really be reveling in all this attention.

What people may not understand is that I fucking HATE this. Even though I write about it constantly, I take no pleasure in talking about my abuse-every time I do it triggers me. My visable scars are a source of shame for me to this day-every morning I have to look at the nose that is slightly off kilter and the scar on my lip, the lines from where that razor cut into my flesh, and I have to confront it again. Every day. It is humiliating to share these pictures publicly. I will probably end up deleting them shortly-but for the time being, you can have a glimpse into what this does to you.

Like most people, I really just want to be normal. But I know I never will be.

In the words of Lawrence Langer, a Holocaust Scholar: "The survivor does not travel a road from the normal to the bizarre back to the normal, but from the normal to the bizarre back to a normalcy so permeated by the bizarre encounter with atrocity that it can never be purified again. The two worlds haunt each other."

But I don’t know how much longer I can do this. Financially, personally, I just don’t know anymore. Because the crime you cannot see leaves very real scars-which can easily break open and become festering wounds again. I’m trying to deal with it while keeping up my momentum, but sometimes it's just too much. And I just want to go back to that life I had before- keeping all of this buried, going through the motions, and existing. I want to slip back into that comfortable numbness again. The only thing that stops me is the fact that so many people are depending on me to keep this going-but I have to be honest, I'm going to collapse under that weight soon.

There is no conclusion to this diary-just a call for help. Please don’t let our voices go unheard. See the crime that remains invisible. Bear witness and then join us to fight for something approaching justice.

But whatever you do, please don't ask us to move on. Some of us never will.

No comments:

Post a Comment