(Originally posted on Daily Kos)

(Originally posted on Daily Kos)I will open this with both a warning, and a bit of an apology-As the title of the book suggests, Judith Herman writes about Trauma. I am a survivor of sexual abuse. The importance of this book simply cannot be discussed without also touching upon some of my experiences with that. I realize this can be an uncomfortable topic, and is not really typical for this series-however, when I was approached about doing an installment for this I couldn’t think of any book that has changed my life more than this one. I also think this book (and hopefully-my review of it too!) is an important read both for trauma survivors and non-survivors alike. For survivors, there are simply no words to explain how much this book helps-it's truly a life-changing read. And non-survivors will come away with a richer understanding and greater empathy for those who have lived through experiences that seem completely foreign and unimaginable. This book forges a robust connection between public and private lives, and does it in a way that can be understood even by those with no background in trauma psychology. Indeed, this is what I found most powerful about Herman's book-it made me feel like I could reconnect with the outside world again.

Introduction

I could tell from the outset that this was not your typical “Healing from Trauma” book. In her introduction, Herman makes it clear that this book will deal with both the individual experience of Interpersonal trauma AND the social forces behind it. When I read she was going to be doing all of this AND doing it from a feminist perspective-something she admits will be "controversial"- I was hooked (and thought "I'm in LOVE with this woman!") In the introduction, Herman also gives us her take on why people try to shun or silence trauma survivors:

"It is very tempting to take the side of the perpetrator. All the perpetrator asks is that the bystander do nothing. He appeals to the universal desire to see, hear, and speak no evil. The victim, on the contrary, asks the bystander to share the burden of pain. The victim demands action, engagement, and remembering."What made this book so powerful for me was that it went beyond case histories, activities, and healing on an individual level. We are social beings, and our existence does not occur in a vacuum-we must interact daily with the outside world. The way our culture regards trauma and its victims is therefore vital to those who are trying to reintegrate into society after profound psychological distress. Dr. Herman explains our modern Western cultural attitudes toward psychological trauma, gives a fascinating and pertinent history of how those attitudes have evolved throughout history, and how they affect individual survivors in their recovery. Dr. Herman sets forth most of this broader cultural history in Part 1, Chapter 1, "A Forgotten History." I am actually doing a 5 part diary series based on this section alone. She begins with the female hysteria patients of 19th Century Europe (which I diaried about here) and ends up with the Vietnam veterans' movement to demand treatment for combat stress reactions. In 1980 the American Psychiatric Association included "post-traumatic stress disorder" in its official diagnostic manual. This led to an understanding that rape, sexual abuse and domestic survivors suffered from a very similar type of distress, and eventually to the acceptance of P.T.S.D. as a diagnosis for them as well. To paraphrase another review, by exploring the dynamics of periodic amnesia, repression and denial, Dr. Herman does a great service to those who must heal and re-enter a culture which can sometimes be as brutal as those who abuse them.

Chapter 2-Terror

Dr. Herman first tackles the subject of terror itself. What does it mean to be terrorized? She first describes what happens when a person is thrust into a traumatic experience-the “fight or flight” mechanism kicks in, causing a state of hyperarousal. This response is almost universal- and everyone experiences at some point in their lives. If you have ever been in a car accident, or been spooked by something, or even watched a scary movie you recognize that your body responds to that feeling of fear- you feel your heart pounding, you may start to sweat and salivate, and your muscles become tense. You get what is commonly described as an “adrenaline rush”-your entire existence becomes focused around the traumatic incident.Your autonomic nervous system primes the body to respond when it perceives a life or death situation-it is truly remarkable how intricate this process is and how every part of the body is involved-from the tiniest capillaries to the brain itself. But in a situation where the trauma is prolonged and the victim perceives they have no way to escape-when someone is held captive, or if they are a child being terrorized by an adult- this ordinarily seamless response becomes overwhelmed and disorganized. And long after the person is removed and returned to a safe environment, the response persists-altering the way the body and mind work in profound and often devastating ways. Dr. Herman goes on to outline the 3 cardinal signs of Post Traumatic Stress Reactions-Hyperarousal, Intrusion, and Constriction. I will briefly describe each of them: Hyperarousal Hyperarousal is often the first symptom-it is a continuation of the fight/flight response. The victim is in a constant state of alert-unable to sleep, startled easily, and their senses are heightened. After the acute stage immediately following the traumatic event, they may slip into a more generalized anxiety, with certain “triggers” that cause them to re-experience the more acute symptoms. Intrusion Something that Freud described as “Idee Fixe”. More commonly, it is referred to as a “flashback”. The victim is unable to return to normal life-they find themselves continuously reliving the event. The memories of the event are often so vivid that they feel as if they are actually happening. The reason for this, as Dr. Herman explains, is because the "Fight or Flight" response causes the release of adreniline and other stress hormones-and it has been scientifically proven that when these hormones are circulating, the memories become deeply imprinted on the brain. Intrusion also takes place within dreams-traumatic nightmares are often very visceral and feel like actually reliving the event itself. Since dreams are reprocessed memories, traumatic dreams are unusual for the same reason that traumatic memories are unusual-the biochemical reactions that occur during trauma leave them deeply engraved in the mind. Finally, the survivor may constantly and compulsively reenact their traumatic experience. This is usually subconscious. Children who have been sexually abused, for example, often recreate scenes of their abuse through play. Adults may find themselves repeatedly exposing themselves to versions of the experience. For myself, I realized that my pattern of reckless behavior-what I describe as my game of Russian Roulette with my life-was a manifestation of this. It is believed that these are attempts to recreate the traumatic memory, and change the outcome. Constriction Constriction often first occurs during the traumatic even itself. Victims often describe this as "numbing out". As Herman explains:

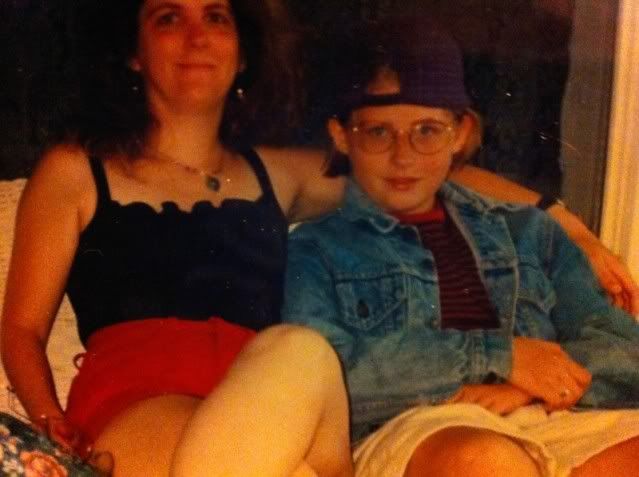

Sometimes situations of inescapable danger may evoke not only terror and rage but also, paradoxically, a state of detached calm, in which terror, rage, and pain dissolve. Events continue to register in awareness, but it is as though these events have been disconnected from their ordinary meanings. Perceptions may be numbed or distorted, with partial anesthesia or the loss of particular sensations. Time sense may be altered, often with a sense of slow motion,and the experience may lose its quality of ordinary reality. The person may feel as though the event is not happening to her, as though she is observing from outside her body, or as though the whole experience is a bad dream from which she will shortly awaken.Reading this was profound for me-because so much of my own abuse felt almost surreal-so much so that I thought I might have imagined it. During most of it, I remember being on the ceiling, looking down at myself. I thought this was crazy-until I read an account from a child sexual abuse survivor describing her own abuse in the exact same way. Another sign of this detachment is emotional-people who have been traumatized often have a dull, flat affect. Their facial expression is described as "The thousand mile stare". My friend and fellow sexual abuse survivor Roxine has shared this picture of herself as a child- you can see the vacant expression in her eyes:

Victims who are not able to dissociate this way on their own often turn to drugs our alcohol to numb themselves. Dr. Herman cites a shocking study on Vietnam Veterans with PTSD-85% of them reported problems with drugs or alcohol after they returned home. Only 7% had been drinkers or drug users before experiencing combat.

Disconnection

In the third chapter Dr. Herman explains the impact that trauma has on the victims everyday life-and how it can result in not just broken minds and injured bodies, but in shattered relationships to those closest to them, the community, and the outside world:

In situations of terror, people spontaneously seek their first source of comfort and protection. Wounded soldiers and raped women cry for their mothers, or for God. When this cry is not answered, the sense of basic trust is shattered. Traumatized people feel utterly abandoned, utterly alone, cast out of the human and divine systems of care and protection that sustain life. Thereafter, a sense of alienation, of disconnection, pervades every relationship, from the most intimate familial bonds to the most abstract affiliations of community and religion. When trust is lost, traumatized people feel that they belong more to the dead than to the living.This helped me a great deal-to explain my feelings of isolation. I have always been a very closed off person-which might surprise people, given how personal a lot of my writing is. In many ways, Daily Kos has provided me a safe outlet-where I was first protected behind the anonymity of a computer screen and pseudonym-to reintegrate myself with the wider world. Reading "Trauma & Recovery" helped me to realize that my tendency towards self-isolation is not due to any character defect-it is a byproduct of shattered trust and ideals. And more importantly, it is something that can be repaired. Herman also explains how trauma can have a devastating impact on the most important relationship of all-the relationship with oneself:

Traumatic events violate the autonomy of the person at the level of basic bodily integrity. The body is invaded,injured, defiled. Control over bodily functions is often lost; in the folklore of combat and rape, this loss of control is often recounted as the most humiliating aspect of the trauma.Furthermore, at the moment of trauma, almost by definition, the individual’s point of view counts for nothing. In rape, for example, the purpose of the attack is precisely to demonstrate contempt for the victim’s autonomy and dignity. The traumatic event thus destroys the belief that one can be oneself in relation to othersThe chapter also deals with the often contradictory nature of survivors relationships-both with others, and the outside world. Because of difficulties modulating intense anger, survivors of trauma often swing between uncontrolled rage and an intolerance of aggression in any form. This also plays out with intimacy-survivors will desperately seek out close relationships, and then withdraw from them completely.This has marked all of my relationships-both platonic and romantic. I tend to form intense bonds with people-but as soon as I start to feel vulnerable, I sabatoge them. I found myself both terrified of being with people, and terrified of being alone. Survivors of trauma lose their sense of connection-to themselves, to their communities, and to the people around them. They lose their faith, and their entire belief system is often shattered. Herman also explains how social status plays a role in the level of disconnection a trauma survivor feels with the outside world. While trauma can have a devastating impact on anyone, the impact is especially brutal when the victim is already disempowered and devalued by society. At the conclusion of this chapter, Dr. Herman makes what I consider one of the most profound points in her entire work here:

Combat and rape, the public and private forms of organized social violence, are primarily experiences of adolescence and early adult life. The United States Army enlists young men at seventeen; the average age of the Vietnam combat soldier was nineteen.In many other countries boys are conscripted for military service while barely in their teens. Similarly, the period of highest risk for rape is in late adolescence. Half of all victims are aged twenty or younger at the time they are raped; three-quarters are between the ages of thirteen and twenty-six. The period of greatest psychological vulnerability is also in reality the period of greatest traumatic exposure, for both young men and young women. Rape and combat might thus be considered complementary social rites of initiation into the coercive violence at the foundation of adult society. They are the paradigmatic forms of trauma for women and men respectively.

Child Abuse

In this chapter, Herman tackles the devastating impact of child abuse. While it may seem strange to have a chapter devoted to singling out one form of trauma over the other-she quickly makes it apparent that the experience of a traumatized child is very different than that of an adult:

Repeated trauma in adult life erodes the structure of the personality already formed, but repeated trauma in childhood forms and deforms the personality. The child trapped in an abusive environment is faced with formidable tasks of adaptation. She must find a way to preserve a sense of trust in people who are untrustworthy, safety in a situation that is unsafe, control in a situation that is terrifyingly unpredictable, power in a situation of helplessness. Unable to care for or protect herself, she must compensate for the failures of adult care and protection with the only means at her disposal, an immature system of psychological defensesShe goes on to describe the ways that children learn to survive in this perilous environment. They become innately in tune with their abuser-learning to recognize subtle changes in facial expressions, body language and demeanor that indicate danger-signals of intoxication, sexual arousal, dissociation and anger that indicate some form of abuse is about to occur. To avoid being abused, they will either avoid or try to placate their abuser. Social isolation is common for these children-a condition that is strictly enforced by their abuser in the interest of maintaining both secrecy and control. This social isolation prevents the child from forming relationships with others who are in a position to help her. Doublethink Throughout all of this, the child is still a child and going through the process of development. This requires the formation of primary attachment. When the abuser is the child's parent or caregiver, they are faced with a profound developmental obstacles:

She must find a way to form primary attachments to caretakers who are either dangerous or, from her perspective, negligent. She must find a way to develop a sense of basic trust and safety with caretakers who are untrustworthy and unsafe. She must develop a sense of self in relation to others who are helpless, uncaring, or cruel.She must develop a capacity for bodily self-regulation in an environment in which her body is at the disposal of others’ needs, as well as a capacity for self-soothing in an environment without solace. She must develop the capacity for initiative in an environment which demands that she bring her will into complete conformity with that of her abuser. And ultimately, she must develop a capacity for intimacy out of an environment where all intimate relationships are corrupt, and an identity out of an environment which defines her as a whore and a slaveThe child has to find some way to explain their parents behavior-whether malice or indifference. This is the only way that they are able to preserve the attachment to their parents or caretakers. To do this, the child often develops a wide array of defense mechanisms, which help him or her deny the abuse is actually happening. Powerless to alter her environment or the unbearable reality, the child alters it in her mind. This process of altering consciousness is clinically known as dissociation, but is also referred to as "double consciousness" or "doublethink" A Double Self Abuse, especially sexual abuse, fills a child with a sense of "inner badness". In order to preserve her primary attachments to her parents, the child will often form a separate, stigmatized identity to take the evil of the abuser into herself. Although I was not abused by my parents, I did form a double identity-I became a boy named Chris. You can see "Chris" in this childhood photo:

This was no mere tomboy stage-those who knew me at that time will tell you that I fully became "Chris"-insisting on being called by that name, even going as far as stuffing the front of my underwear. I needed to become "Chris" so that I could have an identity that was not taking part in this forbidden and shameful activity. The abused child's "bad" inner self is often disguised by their outward appearance-abused children often persistently try to be good. They become obedient, perfectionist, and over-acheivers. At the same time, they repel all compliments about their achievements and virtues-seeing their "performing self" as inauthentic and fake. Positive recognition only serves to make the child feel even more isolated-reaffirming their need to keep their "real" self hidden-for if anyone were to truly know them (the "bad" self) they would be shunned and despised. Some children are able to salvage a more positive identity for themselves, but it often involves extreme self-sacrifice. As Herman explains:

They embrace the identity of the saint chosen for martyrdom as a way of preserving a sense of value. Eleanore Hill, an incest survivor,describes her stereotypical role as the virgin chosen for sacrifice, a role that gave her an identity and a feeling of specialness: “In the family myth I am the one to play the ‘beauty and the sympathetic one.’ The one who had to hold [my father] together. In primitive tribes, young virgins are sacrificed to angry male gods. In families it is the same.In my diary "Thank You Pat Robertson" I described how I became fixated on Saints in my childhood-in particular Saint Maria Goretti. Throughout my life, I have continued to engage in acts of extreme self-sacrifice. This has become my most persistent maladaptive trait-I believe because of my unresolved feelings of guilt over not being able to save my best friend. Reading about this helped me to understand this part of my behavior better. The entire chapter itself also reminded me that I was actually extremely lucky in comparison to what most child sexual abuse victims live through-My abuse did not take place within my own home. It did not involve anyone who I had a primary attachment with, and I was able to preserve those relationships.

A New Diagnosis

Reading chapter 6 was a watershed moment for me. I literally burst into tears within the first few paragraphs-because for the first time, I had an explanation for what was "wrong" with me. Throughout my life, I've had an alphabet soup of acronyms and stigmatized labels used to describe me: ADHD, OCD, ODD (Oppositional Defiance Disorder), Bipolar Disorder, and Borderline Personality Disorder-the mental health equivalent of leprosy. None of these labels ever seemed to fit (I was often told I had "atypical" presentations) and the treatments for them never seemed to work. As I learned in this chapter, my experience was not unique-in fact most trauma survivors who are involved in the mental health system are given a series of incorrect diagnoses. Their failure to respond to treatment often results in a hostile doctor-patient relationship, and accusations of malingering-in essence, they are told they must simply want to be sick. The natural tendency to blame the victim results in pejorative diagnostic labels-originally "Hysteria" was used as a catch-all, but this later evolved into "Personality Disorder". Patients with Personality Disorder are said to have an inherent defect in their character that has been there since early childhood and persists throughout their lives- a characterization that only reaffirms that innate sense of "inner badness" that many abuse victims carry with them. Herman proposes that for patients who have survived prolonged and/or repeated traumatic experiences, a new diagnostic label-Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or C-PTSD. A good summary of the disorder can be found here: Out of the Fog: C-PTSD

The "Complex" in Complex Post Traumatic Disorder describes how one layer after another of trauma can interact with one another. Sometimes, it is mistakenly assumed that the most recent traumatic event in a person's life is the one that brought them to their knees. However, just addressing that single most-recent event may possibly be an invalidating experience for the C-PTSD sufferer. Therefore, it is important to recognize that those who suffer from C-PTSD may be experiencing feelings from all their traumatic exposure, even as they try to address the most recent traumatic event. This is what differentiates C-PTSD from the classic PTSD diagnosis - which typically describes an emotional response to a single or to a discrete number of traumatic events.I will not get into the clinical features of the disorder here, but note that they are the result of the behaviors that were discussed in this diary-those behaviors and traits that help people survive trauma, which become maladaptive once they return to the "real world". Suffice it to say, reading this chapter was like reading a book about my own life-So many feelings and behaviors that had never made sense to me before were transformed and seen through new light. Astoundingly, it has been over 20 years since Judith Herman wrote this book and proposed the C-PTSD diagnosis, and it still has not been accepted by the psychiatric establishment! Judith Herman gives us a bit of insight into the surprisingly politicized process of getting a diagnosis accepted by the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (commonly referred to as the "DSM"), which may explain why. But regardless of it's inclusion, simply having a name for what I had been feeling for all of these years was very therapeutic.

Part 2

Part 2 describes the stages of recovery. This information is very concrete, very helpful, and also reaffirmed my sense of hope that I might be able to live a full life again. Dr. Herman outlines three main stages: establishing safety, remembering and integrating one's story, and re-integrating oneself back into the social world. But perhaps the most important part of this book came in the last chapter Finding a Survivor Mission

Most survivors seek the resolution of their traumatic experience within the confines of their personal lives. But a significant minority, as a result of the trauma, feel called upon to engage in a wider world. These survivors recognize a political or religious dimension in their misfortune and discover that they can transform the meaning of their personal tragedy by making it the basis for social action. While there is no way to compensate for an atrocity, there is a way to transcend it, by making it a gift to others. The trauma is redeemed only when it becomes the source of a survivor mission.For as long as I can remember, I've been trying to channel my experiences into social action-even when I wasn't consciously aware of the link between the two. But I believe that being sexually abused actually made me a liberal. It taught me to distrust authority, and to recognize the dynamics between abuse, power, and oppression. Over the years, the angry spirit that once made me a juvenile delinquent has not been tamed-my anger is always with me, just smoldering beneath the surface, and I believe it always will be. But I've found ways to channel that anger into something productive-through my writing, activism and advocacy. I just never saw how being sexually abused was relevant. It seemed like a very personal issue, and something I should probably avoid talking about. But Trauma & Recovery inspired me to break that barrier between the personal and the political and helped me realize that the very act of talking openly about sexual abuse was in fact a powerful political act. I decided to take it a step further though, and this is how the idea for the organzation TREE Climbers was born:

Formed with my friend and fellow survivor Roxine, TREE Climbers is in it's infancy still (shameless pander-we could REALLY use donations! :D) But our goal is to provide services to other survivors of sexual abuse and exploitation, based on the framework Judith Herman lays out in her book. I won't do a hard sell here or anything but if you want to learn what we are all about please visit our website: http://tree-climbers.org/ And read this diary: Introducing TREE Climbers-The Movement that Daily Kos created And that word-Movement-is important. Because sexual abuse is ultimately about power and oppression-and that is something that occurs on every level of society. Survivors of sexual abuse share so many commonalities in their experiences with other oppressed groups, as well as survivors of different types of trauma from political violence/oppression to military combat to human trafficking. Trauma & Recovery helped me to understand those commonalities, and draw strength from them. Reading it helped me truly move from victim to survivor, and in the process it changed my life-and through the work I do going forward, I believe it will change others lives as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment